The Chirp Jammer: a GPS hit and run

The €50 device that brought a multi-million euro project to a standstill.

You’ve got your base station setup in an open environment, its position has been properly surveyed and it’s tracking signals from all satellites visible overhead with good signal-to-noise levels. What could possibly go wrong?

Here’s what can and did go wrong on one building site of a major construction project. An army of excavators, bulldozers, piling rigs and graders were operating in a confined area with their activities carefully orchestrated by an RTK guidance system. The foreman knew the position of each vehicle down to the centimetre. Without warning, GNSS positioning was lost, warning messages appeared on the screens of the operators’ guidance units and work ground to a halt resulting in days and weeks of machinery down-time and lost man hours.

The culprit: Personal Privacy Devices

The construction site was close to a busy thoroughfare frequented by commercial vehicles whose movements are often monitored by tracking devices that include a GNSS receiver. Such devices ensure for example, that drivers don’t exceed legal driving times or avoid road tolls.

Recent years have seen an increase in drivers turning to cheap GNSS jamming devices, such as those shown in Figure 1, in order to move around undetected or to thwart built-in anti-theft systems.

The problem is that, although these GNSS jammers or PPDs (Personal Privacy Devices) are low power, GNSS signals are even lower power. One PPD powered by a 12 V car cigarette lighter socket is powerful enough to knock out GNSS signals in a radius of several hundred metres. With the increasing use of GPS trackers for insurance or road tolling, the number of jamming incidents has increased significantly in recent years.

GNSS is more than positioning

GNSS applications have long surpassed positioning. GNSS has established itself as part of the critical infrastructure in areas as diverse as cellular communication, where providers use GPS time to manage communications between mobiles phone and phone towers, to banks and stock markets who use GPS to time-stamp their transactions to help prevent fraud.

The effect of Personal Privacy Devices on GNSS signals

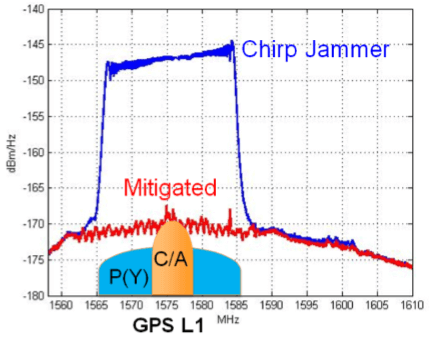

Most cheap in-car PPDs transmit a chirp signal which is a signal that changes frequency rapidly over time. In this way, a signal with a rather narrow bandwidth can cover large swathes of the GNSS spectrum. Figure 2 shows the effect of the signal from a chirp jammer on the GPS L1 band. The region between 1565 and 1585 MHz is dominated by the jammer effectively swamping the GPS L1 signal.

The Septentrio solution against GPS/GNSS jamming and spoofing

Interference Mitigation activated Interference Mitgation activated

The benefit to the user

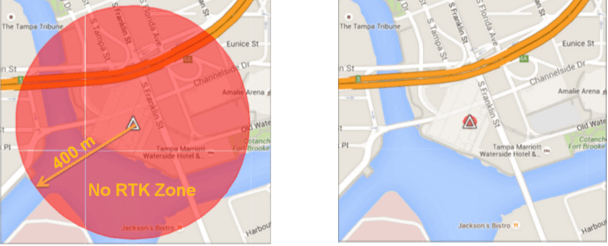

The effects of WIMU are also illustrated in the Figures below. The white triangle indicates the location of a 10 mW chirp jammer in the centre of Tampa and the red zone is the region in which the jammer knocks out the GNSS signal. When WIMU is enabled on a Septentrio receiver for example, the ‘No RTK Zone’ indicated by the red region, is reduced from several hundred metres to a few metres effectively confining the range of the jammer to inside the car it’s plugged into.

Uptime guaranteed

AIM+ technology brings considerable cost benefits to users of Septentrio’s GNSS solutions. Whether in urban or rural locations, on construction sites or piloting a UAS, the detrimental effects of PPDs and other sources of jamming can be considerably minimised thus reducing downtime and costs due to lost man hours.

AIM+ is available on all current Septentrio GPS/ GNSS solutions.

Jamming of GNSS signals is illegal in most countries. If you suspect that jamming is an issue in the area where you work, please report it to the local law enforcement authority.

Related webinar

GNSS hacking, from satellite signals to hardware/software cybersecurity

Related brochure

Everything you need to know about radiofrequency interference (RFI) on GNSS/GPS signals

GPS spoofing - all you need to know how to protect your receiver